MEMBERS

fot. Rafał Placek/ GILDIA REŻYSERÓW POLSKICH

Recipient of the Golden Lion in Venice for lifetime achievement, Skolimowski won numerous awards for direction at leading film festivals worldwide, including Berlin, Cannes, and Venice. He wrote the scripts to Wajda’s “Innocent Sorcerers” and Polański’s “Knife in the Water”. Skolimowski worked in the USA, Great Britain, and Italy. In addition to being a member of both American and European Film Academy, Skolimowski is also a highly regarded painter.

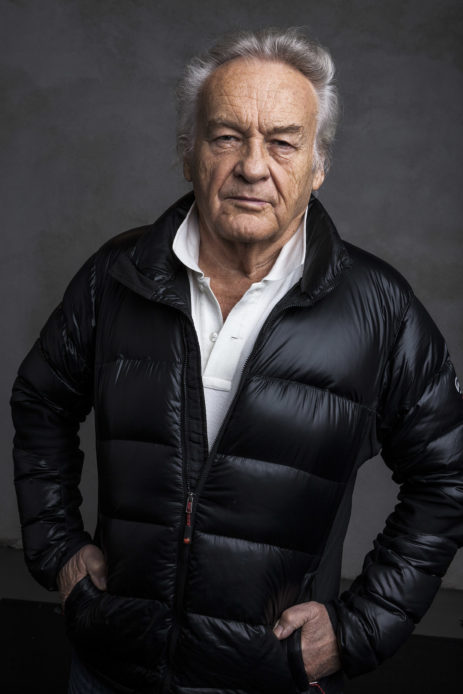

Jerzy Skolimowski

Director – acclaimed worldwide as a virtuoso of Polish film. A regular at the most prestigious film festivals, Skolimowski has received numerous awards at Cannes (Grand Prix du Jury for “The Shout”, Best Screenplay for “Moonlighting”), Berlin (Golden Bear for “The Departure”), Venice (Special Jury Prize for “The Lightship” and Grand Prix du Jury for “Essential Killing”)

Directing movies isn’t his only pursuit – Skolimowski is also an actor (the list of his film appearances includes Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises, Hackford’s White Nights, Schnabel’s Before Night Falls, and even Tim Burton’s Mars Attacks) and painter: he participated in the Venice Biennale, his works were exhibited in Los Angeles, Miami, Toronto, Paris, and Berlin, and are on display in the State Museum at Thessaloniki.

He started out as a prizefighter and poet. A grant from the 1958 Congress of Young Polish Poets allowed him to travel to a writers’ retreat at Obory, where he met Andrzej Wajda and Jerzy Andrzejewski, who were working on a movie script. “They wanted to make a movie about young people; as I was the youngest person at Obory, they asked for my opinion,” Skolimowski reminisced. “After I delivered a scathing critique of their text, Wajda said: So make your own version. I wrote 25 pages of text overnight; it developed into the screenplay of Innocent Sorcerers.”

Skolimowski early pictures were a revelation in 60s. He created a disillusioned portrayal of helpless, flailing young people seeking their place in life and experimenting with cinematic languages

His career took off like a rocket. Admitted to the Lodz Film School, Skolimowski quickly proved exceptional: Andrzej Munk proclaimed his two-minute silent short, The Menacing Eye, “a masterpiece of the silent cinema of the 60s”. “We were a group of friends wishing to use movies to talk about different subjects than contemporary cinema,” the director recalled. “When I was taking my entrance exams to film school, Romek Polański asked me to write the script to Knife in the Water. I spent the days sitting exams and nights writing the script in Polański’s condo. I had the text ready in four days.”

In the second year of film school Skolimowski started working on his directorial debut, Identification Marks: None (1964), a collection of episodic scenes depicting one Andrzej Leszczyc (portrayed by Skolimowski himself), who drops out of school, splits up with a girl (Elżbieta Czyżewska), and goes before the army draft board – all in the course of a single day. The story continues in Walkover (1965) as Andrzej finishes his military service without figuring out what to do in life: he travels from town to town competing in boxing matches until he runs into an unbeatable opponent and decides to skip the bout.

Skolimowski’s next films, Barrier (1966) and Hands up! (1967), were a revelation, a striking contrast to the deeply symbolic conventions of “Polish Film School”. Creating a disillusioned portrayal of helpless, flailing young people seeking their place in life, the director was also experimenting with cinematic languages. “My first movies were mostly intuitive – I didn’t fully realize that directors in other countries, like France or Czechoslovakia, were using similar methods in search of new forms,” he admitted many years later.

fot. Rafał Placek/ GILDIA REŻYSERÓW POLSKICH

Though international audiences interpreted his films in the context of Antonioni movies and the French New Wave, Skolimowski only saw Godard’s Breathless in 1966. “That movie was a turning point in my perception of the cinema. I went on to discover Rivette’s Mad Love and Godard’s later films, particularly Pierrot le Fou,” Skolimowski reminisced. He met Godard at a film festival in New York in the 1960s – the great Frenchman slipped him a note scribbled on hotel stationery that said “We’re the world’s best directors.”

“When I regained my footing and felt fulfilled as a painter, I was able to return to filmmaking – with a firm commitment to never make an average movie again.” He kept his word

While his first three movies were extremely critical of Polish reality and consciously taunted the state’s censors. He moved on to open rebellion in Hands up!, showing a huge portrait of Stalin with two pairs of eyes. The censors demanded to remove the scene, but Skolimowski refused. “They delivered my passport to my place a short while later. The message was clear: get out of here! I had to emigrate – I didn’t have a choice,” Skolimowski reminisced.

Inspired by an anecdote of a diamond found in the snow, Deep End (1970), a German-American co-production, was one of Skolimowski’s first successful endeavors after leaving Poland. His films produced abroad include The Adventures of Gerard (1970) starring Claudia Cardinale, King, Queen, Knave (1971) starring Gina Lollobrigida, The Lightship (1986) with Robert Duvall and Klaus Maria Brandauer, and Torrents of Spring (1989) with Nastassja Kinski. Naturally, he hadn’t forgotten about Poland, appearing at the festival in Gdańsk shortly before the imposition of martial law to screen his formerly banned Hands up! with an added prologue foretelling imminent disaster. “I left Poland feeling disappointed that my voice was just crying in the wilderness,” Skolimowski mused. Shortly afterwards he produced Moonlighting (1982) with Jeremy Irons, a story about Polish laborers working in London as martial law is imposed in Poland. “Irons immediately agreed to take the leading role and we started shooting four weeks after the martial law went into effect,” he recalled. In 1984 Skolimowski directed Success is the Best Revenge about a Polish theater director (Michael York) who escapes to England; one of the plays he stages is about the martial law.

After Ferdydurke (1991), an adaptation of Gombrowicz’s novel of the same name, Skolimowski stepped back from filmmaking. “I decided to take a break from movies. While I hadn’t intended for it to last 17 years, I cut myself off from filmmaking to work on painting. I basically withdrew from the world. When I regained my footing and felt fulfilled as a painter, I was able to return to filmmaking – with a firm commitment to never make an average movie again.”

Skolimowski kept his word. Each of his latest movies was a hit in Poland and abroad. The idea for Four Nights With Anna (2008), selected to open the Directors’ Fortnight section in Cannes, came from his wife Ewa: “We’d read a news item about a Japanese man who was so shy, he could only look at his beloved while she was asleep.” The movie begins like a thriller, but soon turns into a poignant tale of an outsider building an illusion of intimacy with the woman he doses with sleeping pills. It also depicts the very act of watching – a blend of fascination, empathy, and a hint of violence.

The low-key, masterfully formal, and highly acclaimed Four Nights with Anna were shot in the Mazury region of Poland, near Skolimowski’s home and personal artistic haven. This setting also inspired his next famous movie, Essential Killing: “I was driving back home one winter and my car went into a skid. It happened two kilometers from the airport in Szymany where CIA planes would land, delivering prisoners to the secret prison at Kiejkuty. My imagination showed me a prison convoy driving down this very road, getting into an accident which allows one captive to escape. His past isn’t important – the fight for survival is the only thing that matters.”

Essential Killing won dozens of prizes, including the Grand Prix du Jury in Venice and Coppa Volpi for leading man Vincent Gallo, Golden Lions and four other awards in Gdynia, a nomination to the European Film Awards for cinematography, and five Eagles, two of them for Best Film and Best Director.

Skolimowski’s next picture, 11 Minutes, helped him work through a personal tragedy – the death of his son. With a cavalier attitude of rebellious youth, the director assembled a multi-threaded narrative puzzle, bringing the viewer up against a whole panoply of characters in the moments leading to disaster. The nature of the catastrophe remains a mystery: it might be the anomaly that appears in the sky – or the randomness of fate, death shadowing every second of life. Screened in Venice and later in Gdynia, the movie proved surprisingly relevant, touching a sore spot of our modern life: the widespread fear and inescapable sensation of walking on the edge of the abyss. However, it’s also an excellent parable on mediated perception of the reality. “I’m increasingly convinced that we’re looking at images instead of living,” Skolimowski said. “We create and arrange them, filtering the events not through our minds or experiences, but through Facebook and similar media. This isn’t contact, this is just a substitute.”

“I need to make a few more films to prove I deserve this award,” Skolimowski quipped in Venice in 2016 as Jeremy Irons presented him with the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement. “I see this prize as a form of recognition for contemporary Polish cinema – and an encouragement to continue working.”

2015 11 Minutes (feature film)

2010 Essential Killing (feature film)

2008 Four Nights with Anna (feature film)

1991 30 Door Key (feature film)

1989 Torrents of Spring (feature film)

1985 The Lightship (feature film)

1984 Success Is the Best Revenge (feature film)

1982 Moonlighting (feature film)

1978 The Shout (feature film)

1976 Lady Frankenstein (feature film, never finished)

1971 King, Queen, Knave (feature film)

1970 Deep End (feature film)

1970 The Adventures of Gerard (feature film)

1968 Dialogue (feature film)

1967 The Departure (feature film)

1967 Hands Up! (feature film)

1966 Barrier (feature film)

1965 Walkover (feature film)

1964 Identification Marks: None (feature film)

1961 Erotique (school etude)

1961 Your Money or Your Life (school etude)

1961 Boxing (school etude)

1960 Little Hamlet (school etude)

1960 The Menacing Eye (school etude)