MEMBERS

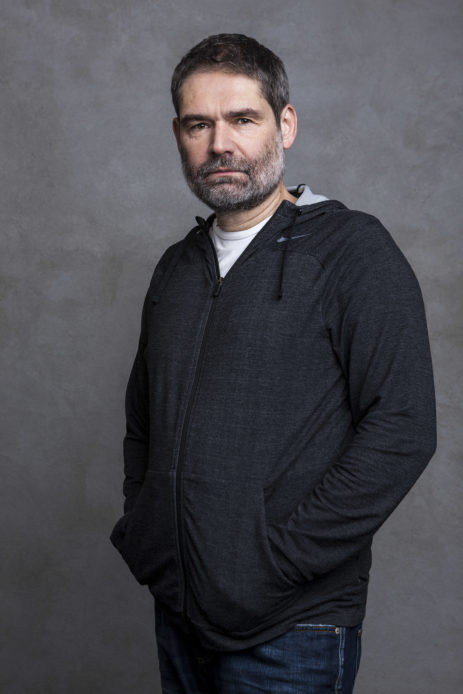

fot. Rafał Placek/GILDIA REŻYSERÓW POLSKICH

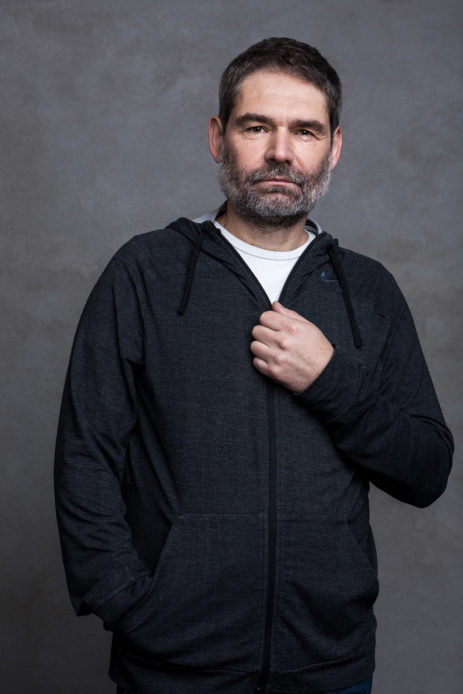

Director and screenwriter. Polish critics greeted his feature debut, “Edi” (2002), with tremendous enthusiasm; the film’s success was reflected in its 11 nominations to the Eagles and a number of awards, including the Ecumenical Jury Prize at the Berlinale. Trzaskalski’s latest movie, “My Father’s Bike” (2012), won an award for Best Screenplay in Gdynia. Trzaskalski is a member of the European Film Academy.

Piotr Trzaskalski

“I grew up in a world where no one had money, everyone wore the same shoes, pants, schoolbags,” says Piotr Trzaskalski. “But you had books and movies that would always be about something important. They’ve instilled in me a conviction that art should deal with important issues. Is war a good way to resolve conflicts? Can we excise hatred from human relations? Is it better to act like Michael Corleone or like Robin Hood?”

Piotr Trzaskalski uses his films to show contemporary Robin Hoods. In a superficial era dominated by everyday drudgery, exhaustion, and mortgages – he creates stories filled with magic. Among ordinary people of modest means, he finds closeness, hope, and warmth. The values he grew up with.

He was born in 1964, in Łódź. His neighbors were the workers from a nearby factory – an engineer, a teacher, an alcoholic, a member of the secret police, and a violinist. And between them all, a jazzman – his father. “Back then, good musicians would end up in flagship hotels,” he recalls. “Dad worked at Centrum. Guests from Kuwait, Iran, Germany, would have fun there with our ladies of the night, who were supervised by the secret police. And the musicians played and observed everything. I grew up on the exciting stories brought home by my father.”

But his childhood was most influenced by the street – “the sacred space” of the courtyard between two four-story-high apartment buildings. Completely lined with cinder, because it looked nice amidst city greenery. “We’d turn over benches to act as goals,” he recalls. “In clouds of black dust, we would play soccer games, cutting our hands and knees on the sharp pieces of slag.” The street was brutal. But it followed an unwritten code from the interwar period. You only hit the other guy until he fell to the ground, and if you picked on someone weaker, “the boss” would kick your ass. These days, people would rather gang up on people when they’re down.

In “Edi”, Trzaskalski told the story of a scrap collector. He painted a realistic background, showing the alcoholism and the poverty, but at the same time wove a beautiful tale about the good in people, about looking for hope and solidarity.

That world also taught him culture. He would spend whole days at the movies – movie tickets cost as much as bus tickets back then. He remembers devouring “Rough Treatment” or French films with Alain Delon and Jean Gabin. On TV, he would “tick off” Russian films with his mother: “The Cherry Orchard”, “War and Peace”, “Come and See”. And out in the courtyard, the boys would tell each other the plots of adult films. “Four guys would go see them at the cinema, and then they’d relate the film to others scene by scene,” he says with a laugh. “That’s how I ‘saw’ »The Road to Salina«, Rita Hayworth’s last film. You went to see the content provided by the socialist state. And back then, the state actually cared that the workers get to see high quality films. Meanwhile, my guide through the world of literature was my older friend Piotrek Polowy. We’d read Norman Mailer’s “From Here to Eternity”, Jones, and of course all the books that had sex in them.”

fot. Rafał Placek/ GILDIA REŻYSERÓW POLSKICH

When he finished high school, his mother cracked open a university guide. She noted that there were only two entry exams that didn’t require mathematics: Polish studies and culture studies. Trzaskalski’s sister chose the first one, he took the other. He wrote stories, ran a cabaret with Krzysztof Skiba, and played guitar in a blues-rock band that even performed at the cult Jarocin festival. After graduating, he decided to pursue directing at the Lodz Film School.

“I figured that if this guitar thing doesn’t pan out, I’ll at least have a job,” he says. “And then film school started, and it turned out that it wasn’t all that easy. I wasn’t a star student. But at a crucial juncture I was told that I was promising. After a badly botched documentary that almost got me expelled, I asked Mariusz Grzegorzek to point me towards some good material. He pulled an armful of books from his bag, and among them I found a short story about an elderly lady that flees from a retirement home under the cover of night. For additional effect, I had her freeze to death at the end. The exam board bawled their eyes out, and I got an A and a scholarship to Leeds, England. And then? Then nothing. Years and years of nothing.”

The early 1990s were a terrible time. Polish film was comatose, directors lost had touch with the audience. There was no money, no institutions, no industry. Trzaskalski found refuge in TV Theatre. After nearly a decade, together with Wojciech Lepianka he wrote the film novella “Edi”, which impressed the producer Piotr Dzięcioł from Opus Film so much that he invested his own money in it.

Film was dominated by dreariness. Trzaskalski didn’t put on rose-colored glasses either. He told a story about a scrap collector, painting a realistic background: alcoholism, poverty, no perspectives, scrap collection centers and gray apartment blocks. But he also managed to use that difficult reality as a springboard. He wove a beautiful tale about the good in people, about looking for hope and solidarity. About redemption.

Trzaskalski’s films look for hope and ask about fundamental issues, about basic human decency. Because, as he says, “It’s a question of your personal code: I’m simply not cut out for vileness.”

Despite “Edi”’s great reception in 2002, he had to wait three years for another chance to helm a movie. And then he made “The Master” – a film that is very much “his”, about a traveling circus performer who meets a woman on the road, but his understanding of manhood, demeanor, and traumas from his past prevent him from pursuing the relationship. “I thought I had an audience that would come to see what I had to say,” comments Trzaskalski. “I wanted to allow myself complete creative freedom, without making any compromises. And so I did. But in the meantime, the Polish Film Institute came into being, and the audience changed, the world moved in a different direction. Festivals told us: ‘It’s interesting, but not really current’”.

The same things that made “Edi” a success now sunk “The Master”. The wider audience wasn’t interested in the magical realism of Polish crossroads and small towns. Trzaskalski disappeared for seven years. He made his living doing commercials, and kept writing. Until he finally returned with “My Father’s Bike”. “It’s my most transparent film,” he claims. “I went for a simple story and I told it as simply as I could. It’s almost sterile style-wise. But I also paid homage to my father and our relationship.”

It’s a captivating story of three men from three generations. There is no anger or thirst for revenge in this examination of relations between a father and a son. There is regret, a mainstay of any profound relationship: regret for all the moments when we didn’t live up to the challenge. And next to them – gratitude and understanding. It turns out that the best props in the world were in his father’s garage. It was there that he found the titular bike that had been passed down in his family from generation to generation. And it was there that he reconnected in the audience.

Currently, he is working on further projects. He doesn’t exactly fit into this world of tacky Photoshopped movie posters and film titles selected by distributors with specific target demographics in mind. A world where you have to pitch and sell your work at industry markets. “But I have good producers: dynamic, multilingual, and worldly,” he says, laughing. He wrote the script “Find Friends” about a Russian soldier in Donetsk who is shocked into deserting by the sight of the casualties of a plane that was shot down. Using a smartphone app, he tries to locate the girlfriend of one of the men who died in the wreckage. The director is also finishing up a text about the poet Władysław Broniewski.

Trzaskalski keeps looking for hope and asking about fundamental issues, about basic human decency. Because, as he says, “It’s a question of your personal code: I’m simply not cut out for vileness. Mark Twain said: ‘If you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember anything.’ And I’m sticking with that.”

2016 Kaprys losu (series)

2012 My Father’s Bike (feature film)

2008 Wróg ludu (teleplay)

2007 Nocną porą (teleplay)

2006 Kryzys (teleplay)

2005 The Master (feature film)

2005 Solidarity, Solidarity (feature film)

2002 Edi (feature film)

2000 Wigilijna opowieść (teleplay)

1999 Dalej niż na wakacje (teleplay)

1999 Żywot Łazika z Tormesu (teleplay)

1998 Walizka (teleplay)

1996 Serce dzwonu (teleplay)

1995 Kotek (animation)

1992 Panienka (school etude)

1991 Pamiętnik z okresu dojrzewania (school etude)

1991 Wlazł kotek (school etude)

1990 W pokojach (school etude)

1989 Discopatia (school etude)

1989 Jasność (school etude)

1989 Tedant (school etude)

2012 My Father’s Bike

Gdynia Film Festival – Best Screenplay

Gdynia Film Festival – The Award of Polish Film Festivals and Reviews Abroad

Gdynia Film Festival – Golden Kangaroo Award of the Australian film distributors

Pyongyang International Film Festival – Special Prize

Tarnów Film Award – Audience Award

Nationwide Comedy Film Festival in Lubomierz – Silver Grenade

“Tofifest” International Film Festival – “Golden Angel” for Best Polish Film

Minsk International Film Festival “Listapad” – Audience Award

Chicago (Polish Film Festival in America) – “Golden Teeth” award for the most interesting feature film

2006 The Master

Trieste International Film Festival – Audience Award

Miami International Film Festival – FIPRESCI Award

2006 Solidarity, Solidarity

Houston (WorldFest Independent Film Festival) – Platinum Award for Independent Theatrical Feature Films & Videos: Historical / Period Piece

2002 Edi

Berlin International Film Festival – FIPRESCI Award in Forum of New Cinema section

Berlin International Film Festival – Ecumenical Jury Award for Best Film in Forum of New Cinema section

Berlin International Film Festival – Don Quixote Award (International Federation of Film Societies Prize)

Gdynia Polish Film Festival – Jury Special Award

Gdynia Polish Film Festival – Journalists Award

Eagle (Polish Film Award) – Audience Award

Warsaw International Film Festival – Grand Prix

Karlovy Vary Interbational Film Festival – Philip Morris Special Award

“Polityka” Passport (Cultural Award of weekly magazine “Polityka”) – Award for Best Film of the Year

Golden Duck (granted by “Film” magazine) – Best Polish Movie

Gold Reel – Polish Filmmakers Association Screenwriters Section Award for Best Polish Film

Cleveland International Film Festival – Main Prize in Central and Eastern European Film Competition

“Prowincjonalia” Nationwide Festival of the Film Art) Main Prize “Jańcio Wodnik” for Best Feature Film

Tbilisi International Film Festival – “Silver Prometheus” Award

Tarnów Film Award – Youth Jury Award

Tarnów Film Award – Audience Award

Split Film Festival – Audience Award

“Prowincjonalia” Film Review – Gold Jańcio (Main Prize)

Lubuskie Film Summer – Golden Grape

Alba International Film Festival – Journalists Award

“Debuts” Polish Feature Film Review – Audience Award

2000 Dalej niż na wakacje

International Young Audience Film Festival “Ale Kino!” in Poznan – Children Jury Prize “Marcinek”

1998 Walizka

Plovdiv International Television Festival – Award of Plovdiv City Council